Deep dive into immersive audio

Join the team for a deep dive into the process of crafting interactive and immersive audio for our virtual reality experience Beyond the Stars VR.

Over the past two years, we’ve been developing one of our biggest projects to date: Beyond the Stars (BTS). BTS is a multi-platform educational program bringing together film, virtual reality (VR), storybooks and mobile games with the goal of inspiring children to adopt healthy eating habits.

Beyond the Stars

A world-first health education program for the Pacific Islands.

Part of the beauty of the BTS project was that almost everything we did was an experiment, and the program’s VR experience was no exception. Given that this was the point in the program when children would be given the agency to embark on their own personalised learning journey, we decided to push ourselves to do something we’ve never done before: make truly interactive, user-driven audio.

In pursuit of this goal, we set ourselves the challenge of not using any music, at least in the traditional sense. Instead, we would have to find ways for the player to construct the music for themselves through their interactions. While we didn’t always succeed in this challenge, we did reveal learnings that will be invaluable for when we try again in the future.

So, in the spirit of sharing those learnings, this interview brings together Jack Condon (game designer), David Grouse (lead developer) and Stuart Melvey (sound designer) as they discuss the conceptual and technical challenges of creating audio that pushes the boundaries of agency and user experience in VR.

To get things started, let’s talk about the idea behind the project. What were the main inspirations for the audio in the VR experience for Beyond the Stars?

Stu: Considering that the game was targeted at kids, we wanted to make it friendly and inviting and colourful. This pushed us in a direction to make the sound design very melodic. We had a few darker references like Stalker, as well as video games like Hyper Light Drifter and Journey that particularly matched the direction of our sound design and gave it a very melodic quality that blended well with the music. I think from the start we were aiming for almost a traditional music score and fit that into the sound design.

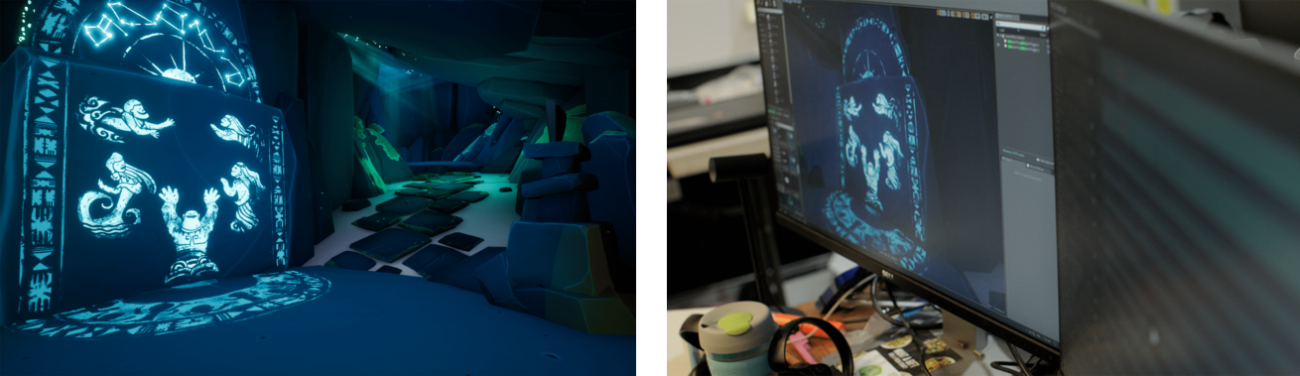

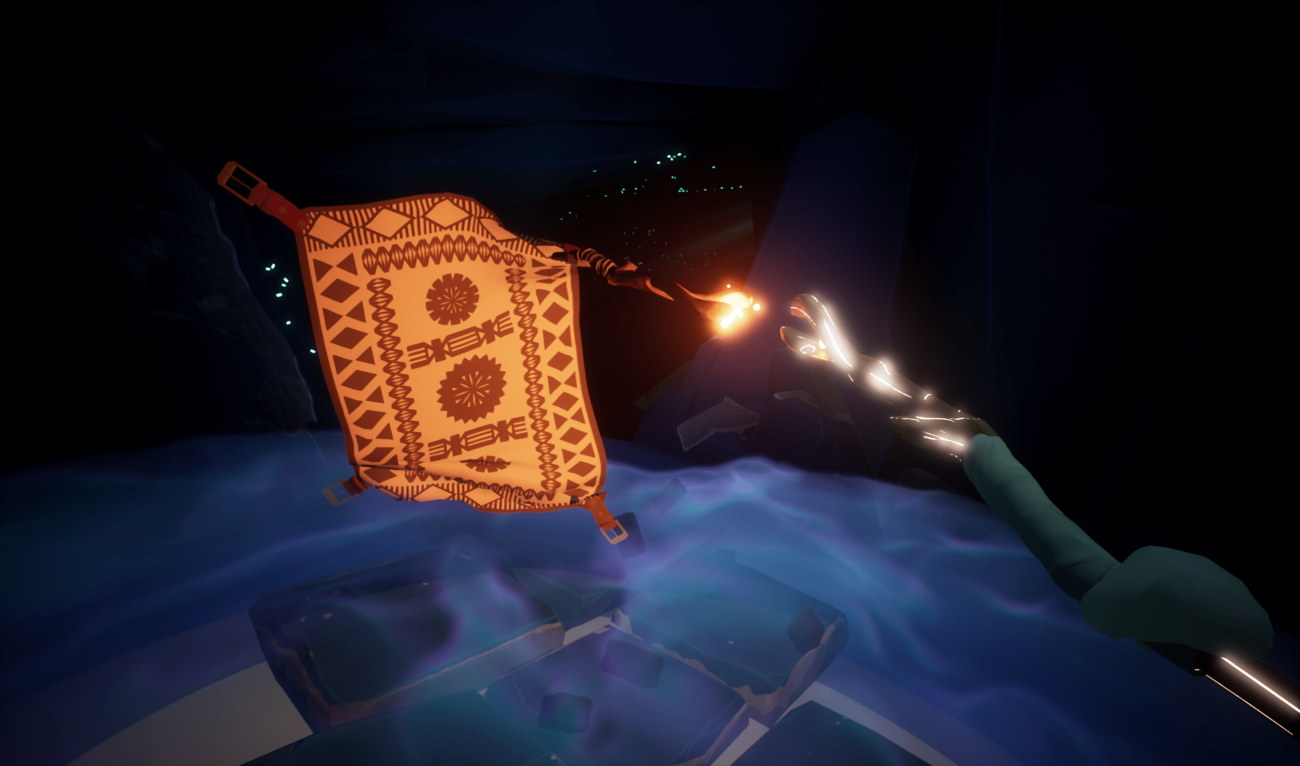

Jack: I think we sampled different things for different reasons. Our connection to Journey was that the focal character makes music to communicate. It’s quite musical, but it ties into your actions. And we were really interested in how that kind of play worked. Disney was another big reference for us, because we have that animated carpet. The first place you go to for that is Aladdin. I don’t know if Aladdin was the right reference, but it was certainly a starting point.

Stu: Certainly, I mean that carpet doesn’t make any noise. It’s a silent carpet. And I guess the biggest challenge is that Aladdin is a linear story and this is not a linear story. It’s up to the player to make the music and because music is very rhythmic and temperamental it becomes difficult to implement.

What was unique to this brief in regards to sound design? What made the project special?

Jack: We set out, really early on, to create a challenge for ourselves. We decided that we weren’t going to use any game audio or game clips. Instead, the audio was going to be both incredibly musical and driven by player agency. For player actions, we would take their normal sound and link it into a procedural musical experiment. We did that all the way through, up until that last 80% when we added music sparingly.

Stu: I think one of the the trickiest things with that kind of music is that it doesn’t really exist as an object in the space. So the more music that we added, the more we collapsed the spatial design. That was a challenge and I think some of the spatial audio, especially the cave sounds, suffered from it. But again, we had to fit the brief and appeal to kids, and music was a great way of doing that.

Jack: I think it’s a really interesting point that you make about those in things being separated in the way we process them. How we process music in this kind of project is fundamentally different, on the perception level. I’m glad we stuck with it, because the sound effect design is really interesting. And ultimately, from a design perspective, it is what keeps the whole project together. It’s like the glue that keeps UX flowing.

Stu: Exactly. From a sound perspective, space and volume is a part of every sound that we hear. We don’t really consider them to be elements in and of themselves – as much as changing the pitch or the timbre of a sound – but they are inherently creative things that we can utilise to tell a story. Because everything must have a volume and everything must have a space.

How was it to have a sound designer on so early in the project’s development? What benefits does it bring to have someone thinking about audio in those very early design phases?

Stu: Sound usually gets push towards the end and in a case like this, I think the project really benefited from having a sound designer on as early as we did. Every project I’m a part of, I like to be involved as soon as possible. Most of the projects I work on, people don’t know a lot about sound, so they either put it off or they don’t really consider it properly. It’s very hard to think sonically when there’s so much else going on. It’s very easy for people to just think “Someone will fix this”. But in this case, there were so many unknowns so it was important for some sounds to get in there as soon as possible. So we could work out what was tragically failing.

Jack: It was definitely an objective for the project to do that. And I think that, just from a development cycle, it was nice to actually get those sounds in and work it out as well. It made development easier, because we knew when sound was working, not just when it wasn’t working. When we knew it was working, that meant we could think “Do we need this particle? Do we need to make this shader, or can we rely on the simplicity of the moment that we already have?”. And to be honest, we wouldn’t have discovered that had audio not been in that early.

In a film, sound and music can be orchestrated very specifically to create the right mood at the right time. That’s not necessarily the case when it comes to games. In that more dynamic environment, how did you make the different beats work with gameplay?

David: One of the challenges we faced was getting the cues to match the player actions. Obviously, when a player swings their stick at the carpet, the carpet is going to drop back. So we’ve got to try and make the music play at that point. But to sync up to the beat, we had to split it up, so that the music was partially delayed and thus able to find the next beat, whenever the player triggered it, and play on that. But we also had to make sure that the action of the carpet jumping back was synced to the interlude that we had. In the end, it needed to be fast enough for the player to really feel they were doing something, and that the carpet (and music) was reacting to them.

Jack: It was a happy solution, whereby we essentially knew and could line up the action where it happened, and just kind of hope for the best. In some instances it was a little bit slow, but I think we get away with it. The music really blends well in the game. We all played it recently, and you can really feel those musical beats line up.

Stu: Definitely. It got a bit mathematical towards the end, but essentially the idea was to create loops of sound. These loops could then be stitched together, so if the player stalls at any moment there’s no cuts in the audio. And over the top, those activated sounds would be in the right pitch and key to what was playing underneath it.

On that note, what would you say are the major differences that you see between the linear audio used in film and nonlinear audio often required by games?

Stu: Well linear is easy and non-linear is unfathomably difficult. There are serious limitations in non-linear audio. Every sound you put in has to be looped and work as an infinite loop. Which means that you end up favouring sounds that have very little excitement, because you can’t hear the same sound repetitively and be interested by it. Once you hear a loop in a game, that brings you out of the experience.

Jack: I think there are major conceptual differences as well, in the way that you approach it. You don’t get to put all the sounds into a track and listen to it altogether. Instead, they get laid out by the player. You have very little control, so you need to be able to conceptually imagine a soundscape where all of these sounds can work and come together to build a musical soundscape.

Stu: Taking that to a grand level, it’s similar to why the game industry is doing so well and the film industry suffering. There’s much more power for the individual to create their experience in a game; it’s very empowering and really exciting for a lot of people. The downside is that a lot of weird stuff can happen when you play a game. Designing a game is a bit like the wild west, see what happens and hope for the best.

But it’s cool knowing that people will have such different experiences from a game that they won’t get from traditional media. I also think that game design now is in it’s very infant stages. Even with larger games with very complex narratives where you almost feel like you’re going through a linear story, it’s not that at all. It’s just a lot of hard work for the game developers to create that feeling.

Sound is obviously quite complex in the Beyond the Stars VR experience. Not only does it have to be beautiful and fit with the landscape, it also has to help guide players move through the game. What do you think was the best implementation of sound as an attractor or motivator in the experience?

David: With attractors we tried out a whole array of different things. Audio attractors essentially allowed us to make the player take a certain action at a certain point in the game. For example, at the start of the experience, we wanted the player to walk over and touch the backpack to activate the next sequence. So we make the bag ruffle in the 3D space so you could tell where it was just through sound. Another example is the carpet mirroring sequence. We wanted the kids to play around with that, to make the carpet would mirror them, but it was the most complicated sound thing we did.

Jack: I was really attached to that sequence as a point of agency in VR, because it’s so amazing to see something mirror you. In that sequence, you end up unsure if it’s you or the stick making the music. Which is kind of the point, in that the idea was to get players to be a conductor of music and sound. That concept was amazing and when you get people to do that they have the best time ever.

We also had a few tonal shifts that helped change the pace from objective-based to more explorative. Making those shifts was really challenging, but crucial to changing the attitude of the player. A good example is when you jump down the portal. That sequence represents the crossing of a threshold: you go from the classroom music to much darker cave audio. There’s no music, just ambiance. But when you pick up the stick, and see the carpet, there’s this wind up that changes the mood instantly.

You’ve mentioned the magic carpet a couple of times now. Can you take us through some of the challenges in creating audio for those sequences?

Stu: We didn’t want to make the carpet too Disney, with really cheesy lollipop whistles and over-exaggerated musical elements. We did go down that path eventually, but the carpet definitely ended up more understated than I anticipated. At the beginning, we were creating a lot of shuffling sounds. But it just sounded so unnatural – carpets can’t make that much sound in a space like that. So we had to look at activated sounds like whistles to give it life instead.

Jack: The whistling. When I first heard it in VR, I remember thinking that this was a great way to direct the player. Because it’s just this beautiful thing to hear your carpet friend essentially whistling across the cave. We had this problem of moving players through the cave, and it was a really hard one to fix. We did so many things, but I think the most successful was giving the carpet the ability to speak.

Stu: Yeah, through whistling and not through a voice, which I think would have broken quite a few rules with not having a mouth. I was at home thinking, if I gave that carpet a voice, I wouldn’t even know what to do. It would have to have a really muffled voice, a speaking-through-carpet sort of sound, so it would be really growly. We tried it out, but that just wasn’t what the character was. And I really enjoyed how the carpet became this kind of friendly, silent helper.

Do you think you’ve learnt the rules of what you can and can’t do in terms of VR audio, or is it more a case of figuring it out with each individual project?

Stu: It’s like anything – the more complicated the systems get, the more complicated the audio gets as well. As technology progresses, it will become simplified and codified so that eventually there will be programs that will do it all for you. But at this stage, new frontiers, a lot of it is pretty grinding.

Jack: For me, I think that this project in a lot of ways was following on the spiritual succession of Kept. The director of this entire project Beyond the Stars came to us, and the original request for the creative drive of this was that it should invoke some of the UX and feeling and design of Kept. And I think you can see that. With Kept, we had just started to learn about what audio could do.

To me, this project was an experiment where we set up all those creative challenges just to test what we could and couldn’t do, what would and wouldn’t work. It was a test to find out how far you could push it. I heard a panel recently, and this sound designer was talking about how audio is 50% of virtual reality. And the amazing thing is that, in this experience, with the way that we’ve pushed it, I’d say it’s more.

In VR, the user journey is really difficult. How do you communicate to the user what they should do in a game that doesn’t have a tutorial? It goes for 5 minutes, and then it’s over. There’s no repeat mechanic. Everything is taught in that moment. And we wanted to see how audio could push that. And I would say that it totally worked.

Kept VR

An interactive story told through room-scale virtual reality.

How has your concept of game audio changed from making this project? What were the key learnings?

David: I actually really liked sound in VR. Implementing sound in VR isn’t any harder than implementing sound in a normal game. But it’s more natural in VR than other games, especially when we placed the sounds at specific locations. In the classroom scene, there were distant waves that were happening softly in the background, and we were really able to spatialise them (through the binaural algorithm that Oculus Audio was passing through). We had to move them down directly to where those waves would be coming from, which was really interesting. And it set up a pipeline for us to think more naturally about where the sounds are coming from. Giving each of the sounds in the experience their own location really sold the realism.

Stu: Yeah. I think we started with maybe 6 to 8 sound objects and then ended up with about 30 in each room. And you need those sounds to fill the space naturally so you don’t notice each individual object. I remember at the beginning, I thought I could just duplicate the sounds and space them out, but that really didn’t work. We had to create each sound with its own loop individually.

My biggest thing with VR is the naturalism vs the virtual fantastical world. You’re inhabiting a space with real physics, and you’re a real person, so the sound has to be somewhat natural. There’s this huge push to make everything feel real and help the player really embody the VR experience. But you’re also in a fantastical world and there are lots of things that don’t sound real. That push to naturalism felt a lot greater than it does when designing for 3D games without VR.

What do you think audio designers who want to work in games need to learn or understand in order to make fantastic game audio? How can someone get into doing this?

Jack: From a production level trying to assemble these teams, it’s really hard to find people who can take on this way of thinking. But it’s not the difficulty that’s holding people back. It’s exposure to that way of thinking, where potentially old tricks won’t work. It’s a completely new space, and you need to approach it with a completely new set of tools and approaches. Anyone who’s interested in game audio needs to dive into the conceptual differences.

Stu: In extended gameplay, you spend so much time with each game that you listen to the same track 40 times. That amount of repetition creates a huge nostalgic element. When you hear a certain melody, you know that you’re safe or you know that you’re in a danger. Considering that repeatability is really important. Sounds in games have to be a little nicer.

When you have someone stabbing a sword 400 times, you don’t want it to be an overly aggressive sound; it has to be cleaner. But again, there’s a lot to play with. Sometimes, repetition can be your friend. People notice the little nuances that perhaps they just wouldn’t in film, because you don’t usually watch a film that many times.

David: It’s all about practice. I like to think of it as a new creative dimension to sound design and implementation. It isn’t linear, and there are so many things you need to take into consideration, it exponentially gets more complicated. But there’s also so much unexplored there, so much creative mystery that’s untapped. For a sound designer, learning the tools and learning what you can creatively work with is the first step. Exploring the possibilities is the next.