Breaking boundaries

With just weeks left to see our interactive touch wall and circular yokai projection at the Art Gallery of NSW, artist Inge Berman looks at how technology is changing the way we interact with the gallery.

After working for a number of years in an industry which straddles art, installation and creative technology, I have been exposed to and inspired by many artists and studios who are using these tools for their projects in fascinating ways.

Boundaries are being obliterated by technical innovations, from intricate hardware manipulations to complex software applications. These experiences have had me running up and down piano stairs, conversing with AI cats and drinking tea decorated with motion sensor activated floral projections.

When entering the halls of a gallery space, it’s amazing to see how technology has been embraced and I am intrigued as to how or if our interactions with these experiences change the way we consume art. Do they reform the way we see or feel? Does this generate different conclusions, understandings or relationships with the artworks and artists?

I have selected a handful of examples being used by exhibitors and artists which highlight some technical innovations designed to shed new light, inspire, inform, educate or augment our gaze within the gallery space.

So without further adieu, let’s dig in.

The OG of gallery tech

If you’re reading this, then I’m sure you’ve sampled an audio guide in a museum or gallery before. When I think ‘tech in a gallery’ my mind immediately goes here, to the little, boxed narrator comprised of an old smeary screened tablet device and corded headphones. That droning voice, explaining the historical context of a Romantic oil painting or an artist who collects black umbrellas. You know, those important tidbits your brain hopefully retains for the next time you’re dragged to trivia. These devices are the first thread I will tug on to unravel the rich tapestry technology is weaving in the gallery space.

Audio tours meet Nintendo at the Louvre

To kick off, we’ll head straight to the Louvre. But first, a short story.

It’s Christmas in 1996 and a family gathers for the festivities. A child sits speechless, her attention glued to a new Nintendo Gameboy, never to converse with family members again – well, at least until the batteries run out. 20 years later this same child (me, if you hadn’t guessed) gazes starry eyed with the same amazement at these same (yet upgraded) devices being used by the Louvre for their guided tours.

Commissioned by Nintendo, the Louvre in Paris is decked out with hundreds of these dual touchscreen Nintendo DS gaming platforms. These devices go far beyond your everyday discman. Complete with a fully interactive navigation system, the Louvre’s labyrinthine hallways become a game in themselves as users can program their own trajectory to seek out their idolised pieces of art. Containing more than 600 photos, 30+ hours of audio commentary, 3D interactive models, interviews and trivia, these handheld devices become their own personal Louvre enchiridion.

There is so much content on these devices that Nintendo actually released the program and sold it as a stand alone game. Opening up the Louvre doors to anyone within arms reach of a Nintendo DS, sharing hundreds of years of art and history with people who may never have had a trip to France in their sights. Sacrebleu!

A tour that knows where you are?

If all of the previous information about the Lourve’s tour guide devices didn’t spark excitement and convince you that this is the future, the Nintendo device is also integrated with Bluetooth beacons which track your location to throw information at you based on artworks within proximity. Brooklyn Museum is also using Bluetooth beacons, and they have dedicated staff at the ready to answer your questions appropriately based on your location within the gallery. But most importantly, these devices make it incredibly easy to cheat in a game of hide and seek.

Get ready to heAR about AR

You should be. Augmented Reality (AR) is becoming a common household tool for viewing the world through a different lense. We see it used extensively in the high art forms of Snapchat, Instagram dog face filters and Pokemon Go, but how are we seeing it augment the reality of the gallery?

Companies such as Eyejack and Artivive are creating platforms which can identify ‘markers’ using a smartphone’s camera, activating a superimposed overlay on top of what we see through the lens in real time. Any uniquely identifiable image can be a marker, which makes paintings a perfect candidate. The result? Well, all the Harry Potter fans out there are in luck – paintings can now come to life, like portraits in the corridors of Hogwarts.

This is exactly the approach the Art Gallery of Ontario took with their ReBlink exhibition, where visitors can watch old masterpieces spring to life through a tablet. The spin they took was to situate their subjects in contemporary contexts, i.e. holding smartphones or takeaway coffee cups. I am displeased to report that the portrait characters failed to bring their keep cups – come on guys, it’s 2020.

So, how does this change the way we view art? Does the animation of the subject or its disconnection with the frame create a stronger empathetic link with the viewer? Does it make viewing art and imagining historical context easier? Does it engage younger children with art? Or are our attention spans becoming shorter as we’re oversaturated with content? Who knows!

Digital vandalism with augmented reality

AR technology is getting more and more sophisticated in many ways. One of those ways is how depth cameras are being used to identify the position of objects in the world to determine collision or occlusion. My favourite example of this in the wild was created by a gang of digital hoodlums who have ‘graffitied’ the interior of MoMA. Affectionately called MoMAR, visitors can view the gallery through their smartphone’s camera and experience digital overlays of tags, scribbles and conceptual commentary by these guerrilla artists. Innovation like this really shows the freedom, capacity and potential of digital real estate.

I believe these are the beginnings of how AR will continue to become more integrated in society. Before we know it, AR glasses or contact lenses will be commonplace, and everyone can be on a separate channel of their own silent disco.

A new take on old art

This is the part where I get to speak about the project we, at S1T2, created for the Art Gallery of New South Wales. The piece which inspired me to write this article.

For their 2019/2020 summer show Japan Supernatural, we were asked to transform a historic, 6 metre long Japanese handscroll into an interactive projection. Hiroharo Itaya’s ‘Night procession of the hundred demons’ shows a playful parade of Japanese ‘yokai’- supernatural monsters, demons and spirit’s – that we bring to life through projected animations and conductive ink.

Japan Supernatural

Interactive touch wall brings historic masterpiece to life.

By painting conductive ink touch points onto the wall and projecting our animations over the top we created an interactive art work. I love the irony of a touch-activated artwork on the gallery wall, a place where ‘do not touch’ is usually the standard. It brings a sense of intimacy with the work, where the viewer and the artwork now exist within the same world.

As legend states, many of the spirits Itaya paints were once household objects, now come to life after years of inactivity. Bringing animation to such an energetically painted watercolour makes me ponder on Itaya and his original intentions with the piece. I would love to know what he would think if he saw the way we lovingly gave life and motion to his characters. How we animated his inanimate scroll, which was based on animating the inanimate – try saying that 10 times over.

Frankenstein, Dali + Deepfake

When I digitally animate, I feel like I am creating life. There is a certain ‘mad scientist’ temperament that comes with the practice, when your creation is so convincing you involuntarily rise from your chair screaming “IT’S ALIVE!”

The most Frankenstein-esque example I have come across is a work created by Goodby Silverstein & Partners, where they (pretty much) managed to bring an artist back from the dead using machine learning, AI and a screen. Indeed, Salvidor Dali lives on in a life-sized panel in the Dali Museum, Florida, where visitors are invited to speak with Dali, ask him questions and gain responses.

Made by analyzing over 6,000 frames of archival footage, deep fake artificial intelligence techniques were used to create an interactive version of the man himself. The computer learns about what he looks like, how his mouth moves as he speaks, his eyes and eyebrows and all of the little subtle mannerisms that make up his expression. Not only this, through extensive research on his writings and thoughts, machine learning has been used to generate authentic responses. Every part of his response is generated by fragments of footage and data of him.

For a man so interested in bleeding edge technology in the 20s and 30s, I like to think Dali would be thrilled to know he has been recreated, a digital rendition of his former self constructed of the fragments he left behind. If you ever find yourself in Florida, you can ask him how he feels about it yourself!

Tech outside the gallery

Now, let us dissolve our bodies and float as a consciousness through an endless sea of zeros and ones. Or, in other words, don a virtual reality headset. Virtual Reality (VR) has definitely been a hot topic for years now, but how are gallery curators and artists using this tech?

LiDAR scanning and 3D modelling is already being used to recreate existing artworks and even entire galleries, making them explorable in VR. The Kremer Museum has meticulously scanned and digitized a vast collection of Dutch and Flemish paintings, situating them in a completely fictional space designed by architect Johan van Lierop. These scans are becoming so hyperrealistic that even the textures of the brushstrokes on the canvas are clear to admire in the digital recreations.

This form of digitising is a huge step forward in art accessibility. Organisations such as Malopolka’s Virtual Museum, Cultural Heritage Imaging and many more are using LiDAR scanning, photogrammetry and 3D modelling to upload their artworks to platforms such as Sketchfab for public access. Many of these platforms allow users to zoom, pan and rotate around 3D replicas of these pieces, as well as view them in VR. For me, the most exciting part of this is they can be accessed from a home computer or smartphone, so you can cancel that trip to Rome and buy a VR headset instead!

Games in the gallery

That said, we don’t need to don a VR headset to delve deep into the digital. Videogames have been a powerhouse of immersive experiences for decades, and the Tate Gallery has cleverly adapted one of this century’s most consumed platforms to their exhibit. In recent years, the Tate has used sandbox game Minecraft to create virtual worlds inspired by locations depicted in their collection. Taking Christopher Nevinson’s cubist/futurist rendition of 1920s New York from ‘The Soul of the Soulless City’ into stylistically ‘blocky’ Minecraft maps seems the perfect way to afford audiences the chance to explore the location in a different and contemporary light.

Enter, the ‘Experience Centre’

Amazingly, many of these technological techniques are being used in tandem, creating entire areas within galleries purely devoted to generating these alternative, technology-driven experiences. Companies such as TeamLab design entire touring exhibitions adopting all different technologies to create digital art theme parks known as Experience Centres.

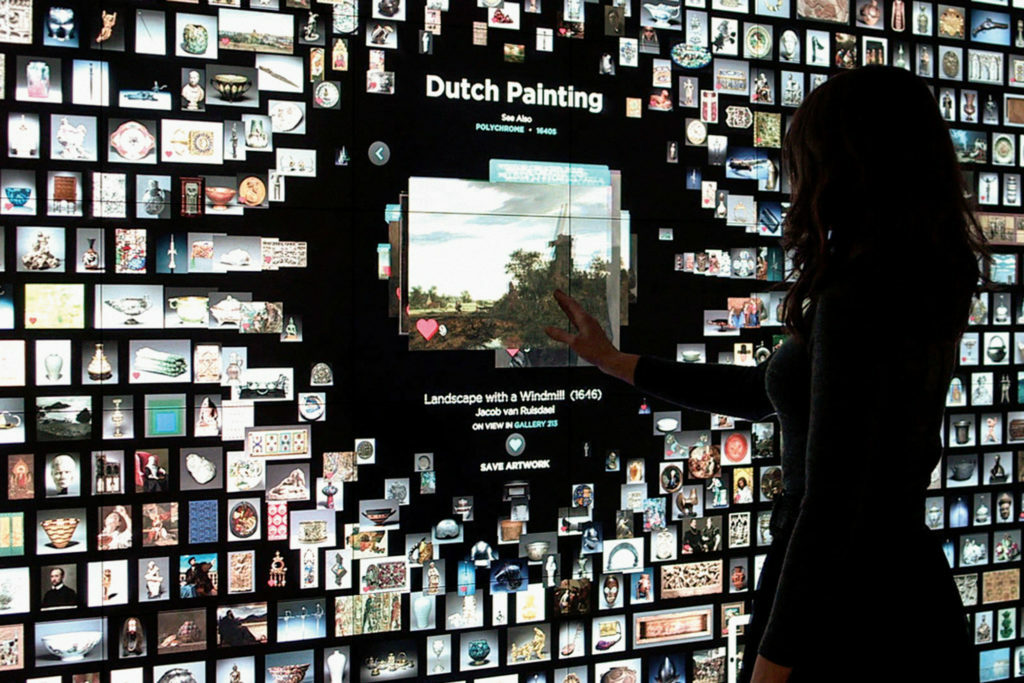

The Cleveland Museum of art is a perfect example of a gallery that has fully embraced this kind of technical integration. Launched in 2012 as Art One and rebranded to ARTLENS in 2017, the space uses works from the museum’s collection creating interactive experiences with touch screens, projection, motion tracking and facial capture.

Another example are the large-scale interactive galleries toured globally by Grande Exhibitions. Known for their high-definition projection works – many of which are interactive – they’ve generated a number of exhibitions based on fine artists throughout history including Van Gogh, Leonardo Da Vinci and a selection of French Impressionists.

A few closing thoughts

So what does this all mean? It means we are effectively living in a Sci-Fi novel. Wherever the tech wind blows, art will follow. From the smaller, smarter and faster to the grand, enveloping and experiential, technology is becoming more imaginatively and commonly integrated within our lives.

We are living in an age where many of these innovations are still new and experimental. The tech cowboys are troubleshooting their ways ahead, opening our eyes and imaginations to the possibilities to come.

Do we like these augmentations of our treasured artifacts or is it dulling the minds of our black mirror dazzled youth? My opinion? Don’t worry too much, and instead enjoy the digital playgrounds being offered to us.